Disillusionment Dharma

Part I

This morning I got up and, as usual, hauled myself out of bed, made my way down the corridor, and sat down on a pile of cushions to meditate. I read a little first – just to clear my head, to sweep away the confusion of nocturnal images – and then put the book down, lit a candle and, as the sun rose, sat and followed my breath.

Whilst I meditated, I found myself asking myself why. Why was I there, sitting on the cushions, watching my breath? To what end? What was it all for? No answer to the question came. I returned to my breath and continued to sit until the sun had risen over the trees. Then I went to drink a mug of coffee.

This question: why bother? has puzzled me for a long time. Even more puzzling is the fact that I still do bother, that I still get up in the morning and sit in meditation, watching my breath, most of the mornings of my life. This is something of a koan – a knotty Zen paradox – for me. I still do this, even when I am utterly disillusioned with Buddhism. For Buddhism has not led me towards the truth. It has not shown me a bright, clear path to a better world. I have not attained much in the way of wisdom.

I am disillusioned with the endless flow of Buddhist books churned out by the presses month after month.

I am disillusioned with the pronouncements of Buddhist teachers who set themselves up as moral exemplars, a disillusionment that is only augmented each time a new scandal – sexual, financial or what-have-you – hits the headlines. Perhaps there is such a thing as Enlightenment; but I have no idea what it is, nor whether any individual I know is remotely close to this state.

I am disillusioned with the Buddhist texts from previous eras with their baroque and florid imagery, their bizarre cosmologies, their obsession with the absurd doctrine of rebirth, with the dewy-eyed lionisation of the Buddha.

I am disillusioned with the fantasies of the mystical east, with the restless desire for some kind of other world beyond this one, with the sickening profusion of gods and goddesses.

I am disillusioned with all pretensions to piety…

But above all, I am disillusioned with myself. My practice of ethics is rudimentary. I have not mastered my desires neither have I gained control of the turbulence of my own mind. I have not conquered the fear of death. I do not have much in the way of compassion.

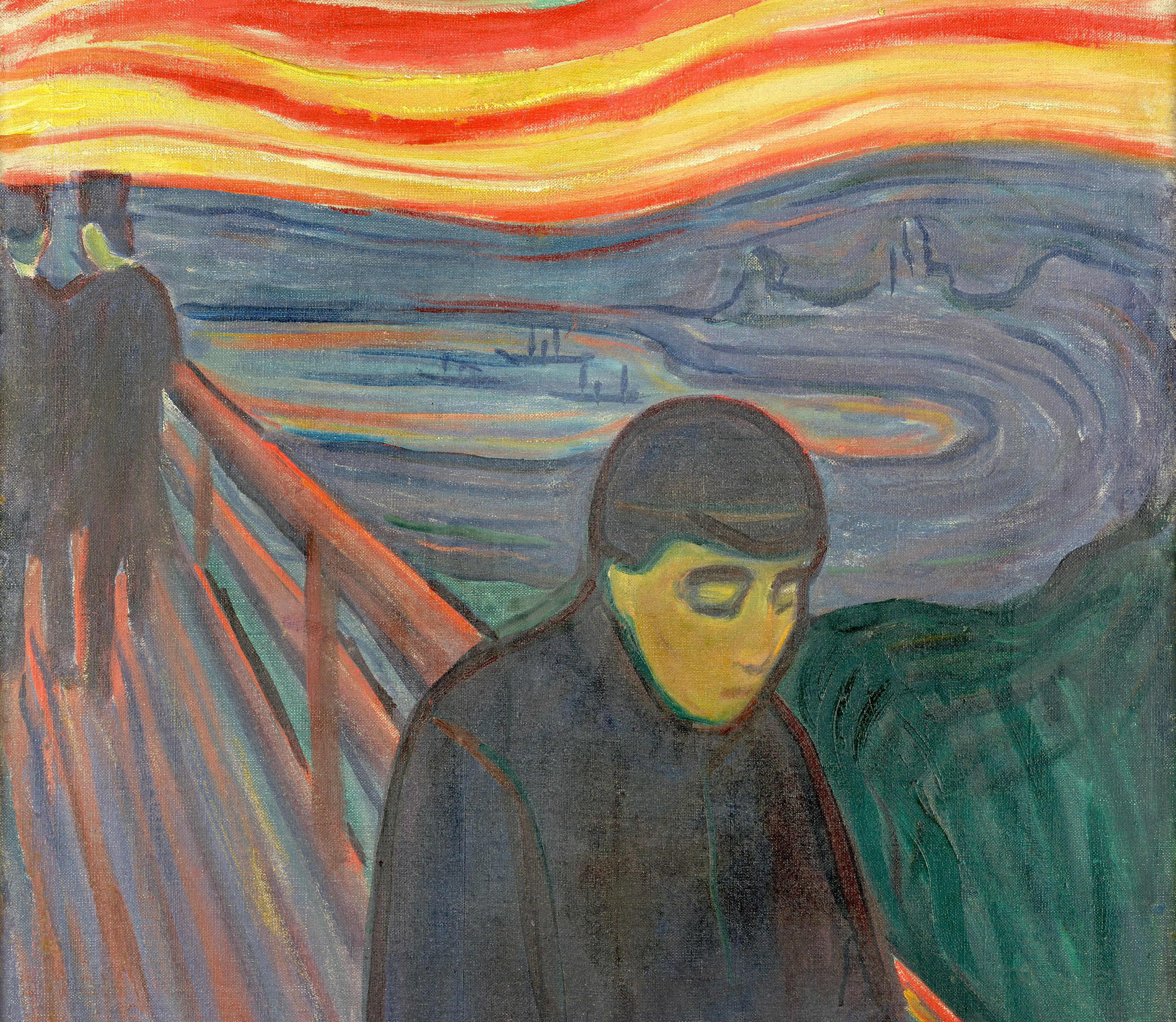

Of course, I could try harder: but when I see those who are rigorous in their practice of ethics, I cannot help noticing a terrible strain, a self-consciousness that seems to border on self-obsession, a surfeit of carefulness. Then there is meditation: no doubt my meditation practice is weak and lax. Although I sit to meditate most mornings, as often as not my mind is distracted, my chin falls forward onto my breast, I nod off to sleep or fall into the most pleasant daydreaming; or else I am taken by the desire to go and do something more interesting. But when I look at those who spend their days meditating, I am frightened by their serene smiles, unnerved by their slow, deliberate speech. As for wisdom, I do not know what wisdom is, but it seems to me to be in short supply. Those who claim to have it, as often as not, fail to impress. And every day I can count up one hundred unwise things that I have done.

I am forced to conclude that there is not a single spiritual bone in my body. I lack the requisite faculties to be a Buddhist. I do not have the aspiration. I am inadequate to the task. I am clay, earthbound. If I believed in rebirth, which I do not, I could comfort myself with the thought that this life might be simply a preparatory one, hanging around on the fringes of Buddhism, so to speak, waiting in the hallway so that I might give it a proper shot next time round. But this life, it seems to me, is the only life there is; and thus I cannot draw comfort from this.

Such is the extent of my disillusionment, that I tell myself I should give up. I should put my flirtation with Buddhism behind me. Sometimes I wonder if I have already given up, but the awareness of the fact has not caught up with me yet. But then… most of the mornings of my life, I stumble out of bed, down the corridor and sit upon my cushions to meditate. Why? Perhaps, it occurs to me, this disillusionment is a sign that my Buddhist practice has not been in vain: a sign that it has been working…

Part II

How, so? After all, it seems that I can’t really get away without justifying this rather cryptic claim.

My dictionary has the following for ‘disillusionment’, which might get things started:

Disillusion noun the state of being disillusioned or disabused; loss of a cherished idea or belief. Disillusion verb trans. to reveal the unpleasant truth about somebody or something admired, to disenchant.

We live, I think, in disillusioned times. It is possible to trace through the last few hundred years the falling away of one after another of the cherished beliefs of the past. It was Immanuel Kant who stripped reason down to size, and brought us the uncomfortable realisation of the limitations of human understanding. Darwin put us firmly back where we belong, as a part of the animal kingdom – curious animals, to be sure, but animals nevertheless. Then Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God and of all higher ideals. Looking back, this seems prescient: in the 20^th^ century and into the 21^st^, the endless procession of wars and atrocities has made any belief in the historical progress of humankind, and any claims to the nobility of humankind, seem shaky indeed.

It is perhaps partly true that the staggering success of science has played a central, perhaps the central role in this process of disillusionment. Has science disenchanted the world? Perhaps. But as far as I see it, the scientific picture of ourselves and our place in the universe is simply the best game in town. Nothing else even comes close. There is no other world picture that accords so closely with how things seem to be. There is no other picture that has been so consistently successful. There is no other picture that is so persuasive. Unlike religion, science demands that any idea should be tested, or at the very least testable. It makes predictions, and then it follows up these predictions by finding out if this is truly the case. Religion doesn’t do this. As an explanatory tool, it simply cannot compete.

In the fact of this disillusionment there are several possibilities. It is easy for disillusionment to seem like a problem in need of a solution. The first response to disillusionment is a kind of weary cynicism, the cynicism of the doomed: we know that there is a problem, but we are so disillusioned that we don’t believe there is a solution. The second response is to engage in a process of what might be called reillusionment. It is my suspicion that this is what is often going on in the practice of Buddhism in the West. Alarmed by the picture we now seem to have of our place in the world, frightened (and justifiably so) of cynicism, the cultural forms of traditional Buddhism can offer a rich resource of reillusioning the world. Instead of God we can have Enlightenment; instead of the saints, Bodhisattvas. This second response accepts the idea that there is a problem, and then solves it with more of the same: different beliefs, different gods, different kinds of redemption come to fill the gap. But the third – and perhaps the most difficult – response is to fully embrace this process of disillusionment.

Buddhism has always set itself against our illusions: our illusions of permanence, our illusions of having a fixed and enduring ‘self’ buried somewhere within us; and our illusion that it is possible to live in a world where we can avoid the necessity of suffering, that we can bend the world to our will so much that we will no longer find ourselves frustrated, miserable and afraid. What if we follow this disillusionment to the end, allow it to gnaw away not only at our cherished beliefs about ourselves, but also at our cherished beliefs about Buddhism? Buddhism, like us, is neither fixed, nor does it have an enduring essence, nor is it satisfactory. Perhaps we need to look into the heart of this flux, this lack of essence, this unsatisfactoriness, in Buddhism as much as in ourselves.

The Kimattha Sutta has the following to say on the subject of disenchantment.

“And what is the purpose of knowledge & vision of things as they actually are? What is its reward?” “Knowledge & vision of things as they actually are has disenchantment as its purpose, disenchantment as its reward.”

Disenchantment as a reward for knowledge of how things are! How can disenchantment be a reward? Because the world continues, with or without our illusions. It is all we have. It is the only thing that there is, the only thing that is real. And returning from our illusions, giving up on our illusions, returns us to the world: not ideas about the thing, as Wallace Stevens once wrote, but the thing itself. How could any illusion that my poor mind could concoct equal – in its staggering richness – the world that it masks? I am beginning to wonder if Buddhism is about disillusionment, and nothing else.

I do not think it could be possible to be entirely disillusioned, to be without illusions altogether; but it does begin to seem as if the perhaps unending process of disillusionment is something not to be feared, but to be celebrated. This loss of cherished beliefs – about ourselves, perhaps about Buddhism also – returns us to the world, in its unarguable richness. This third response is disillusioned with the very idea that disillusionment is a problem. And, as such, it manages to escape the need of any solution whatsoever…